Launching a legacy

Friday, August 11, 2017

Phyllis Bowen, professor emerita in the Department of Kinesiology and Nutrition, sees obstacles and success as two sides of the same coin. Her greatest career challenge was building the department, formerly the Department of Human Nutrition, from scratch. But ask Bowen to name her favorite story of success and the answer is the same: “Building the department from nothing!”

It’s clear from Bowen’s long and impressive career that she’s not the least bit scared of blazing trails or getting down to the tough business of hard work. As a child growing up in Philadelphia, she spent many hours outside, inventing meals that could be cooked over a campfire or Bunsen burner. By the time she was 11 years old, she was preparing every meal for her family of four while her parents worked.

Despite this early propensity for cooking, nutrition was the furthest thing from Bowen’s mind. She wanted to become a doctor, and she pursued this plan at Graceland College in Lamoni, Iowa. It wasn’t uncommon for Bowen to be one of only a handful of young women in a classroom full of men. Unfortunately, gender stereotypes were alive and well in 1958, as Bowen soon learned. People frequently stated that her chosen career would ruin her.

Bowen brushed off their judgment and followed her own heart. That meant plenty of socializing and a busy dating schedule on top of classes and studying. But after two years at Graceland, Bowen started to question her path. For one thing, she was earning Bs in her courses, which made the possibility of medical school less likely.

“Guys could get into medical school with Cs, but girls had to go above and beyond,” Bowen says. “That was very discouraging.”

Secondly, she was having doubts about squashing the bubbly, voluble side of her personality.

“At that time, you either had a career as a spinster doctor or you had a family—you couldn’t have both,” Bowen explains. “I thought to myself, ‘Do I really want to do this?’”

The answer, ultimately, was no. Bowen regrouped, transferred to Iowa State and enrolled in the home economics program. It might sound like a huge transition to shift into home ec from pre-med, but it really wasn’t. There were plenty of food science courses, and Bowen took all of them. She ended up meeting her future husband at Iowa State, and they both pursued Ph.D.s at Cornell University; he in physics and she in nutrition.

“I found that I could have a family and still have the intellectual life that I wanted,” Bowen says. “Even when I was pre-med, I was always more interested in the research side of things.”

Ladies who launch

In 1983, Bowen landed at UIC, and she stayed there for the rest of her career. It was the perfect fit for a young go-getter with energy and ideas to spare. When she arrived, armed with a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Department of Human Nutrition was in its infancy. There wasn’t even a laboratory at first. Luckily, the department head, Dr. Savitri Kamath, who Bowen calls her “partner in crime,” located two basement rooms that Bowen could make her own. Bowen remembers interviewing secretary candidates who declined the position because the space was so dingy and, in their view, scary.

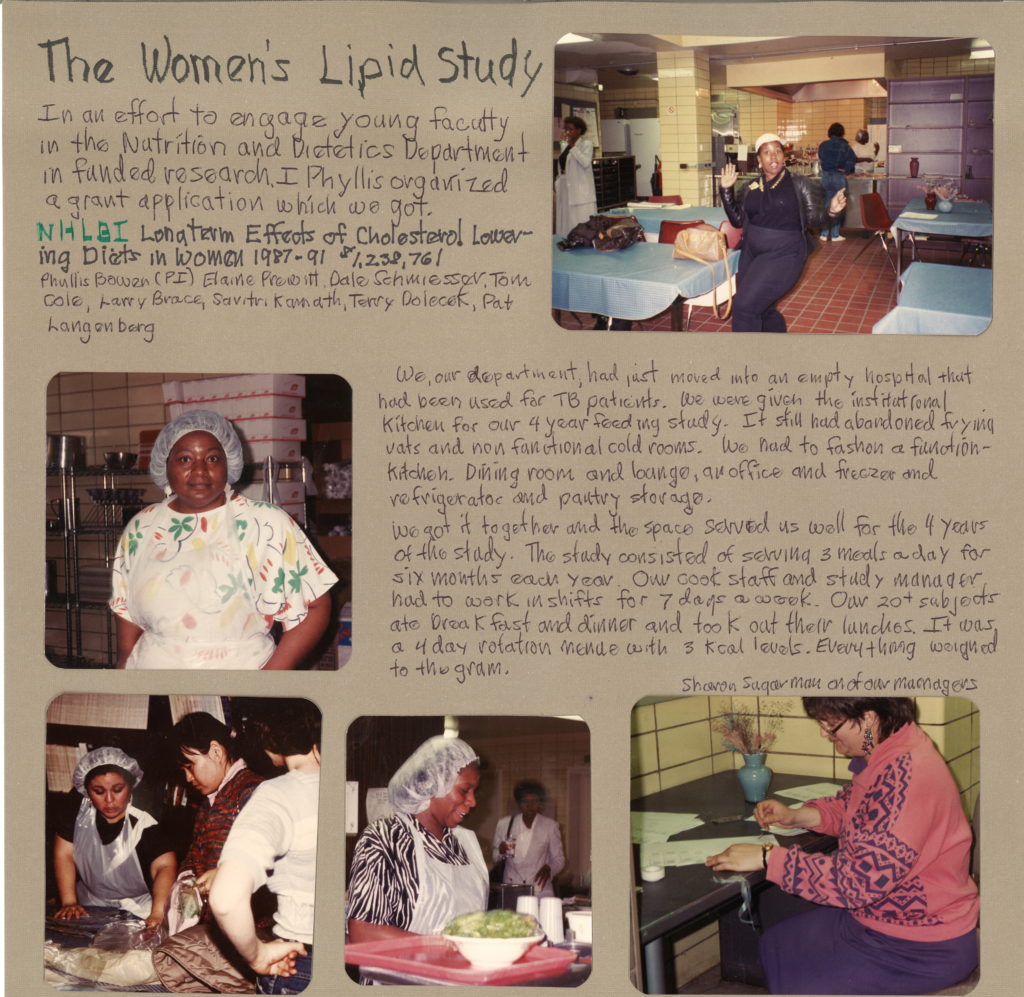

A few years later, the department found a new space in a former tuberculosis hospital building now known as the Applied Health Sciences Building.

“There were still beds in the rooms,” Bowen recalls. “The kitchen still had the old fry vats with oil in them.”

But the team rolled up their sleeves and got to work. Bowen and two other faculty members wrote an NIH grant proposal for an ambitious four-year study on cholesterol.

“We said we would feed pre-menopausal women in our feeding laboratory—which we did not have,” Bowen says with a laugh.

When the grant came through, they asked the university to finally clear out the hospital space, kitchen oil and all. Bowen was staying busy with plenty of other projects besides the feeding study. In particular, she helped launch the carotenoids field, which focuses on red-, orange- and yellow-colored pigments produced by plants, algae and some bacteria and fungi. Among other contributions, Bowen helped establish an international society in experimental biology for carotenoids.

“In addition to putting out papers, writing grants and teaching classes, I was also responsible for developing organizations and conferences to help other people join in investigating carotenoid compounds like beta carotene, lycopene, lutein and so on,” Bowen says. “One of our first monographs was about the measurement of carotenoids because it was all over the place.”

Indeed, Bowen’s lab became a reference lab for the standardization of carotenoid measurement.

The Functional Foods for Health for Research was another highlight. Bowen served as co-director and co-founder of the organization, which connected researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign with researchers at UIC. The cross-collaboration meant both universities could have a bigger impact. Industrial affiliates, such as Monsanto and ingredient companies, came on board as supporters, while annual conferences gave students opportunities to promote their research and network.

As the department began to make a name for itself, in no small part thanks to Bowen’s efforts, the caliber of the faculty and student body rose accordingly. Bowen helped fight for the establishment of a master’s in science in nutrition degree, arguing that the master’s in applied nutrition degree didn’t accurately reflect the intensive biochemistry components of the program. The addition of the M.S. degree, as well as the Ph.D. in nutrition championed by Dr. Bob Reynolds, elevated the department’s stature further.

“They were game changers,” Bowen asserts.

Despite her very full plate, Bowen agreed to help launch the Urban Allied Health Academy, now the Health and Diversity Academy. She served as associate dean of the academy, which prepared students from across the college to serve in diverse communities.

“So many of our students came from so many different backgrounds, and there was this issue of integrating them into understanding different cultures, especially since most of the students were going to end up working in multicultural Chicago,” Bowen explains.

Bowen developed programming on urban health issues, created brochures and led a book club, where she saw students from different disciplines make important connections.

“You can get so focused on your single subject area that you forget that you’re dealing with a whole individual, a human being,” Bowen says. “The book club was a rich experience for our students in that way.”

Grateful gifting

Students were always at the center of Bowen’s UIC experience. She often reflects on how wonderful each student was and how delightful it was to mentor these talented scholars. At one point, a graduate and former student approached her after a speech to let her know that it was because of Bowen that she pursued a Ph.D.

But Bowen also remembers the students who struggled. For the past several years, she has been tutoring a high school student from the Austin neighborhood of Chicago. The young woman is bright, but her family can’t afford to send her to college.

Bowen and her husband are helping their own grandchildren through college, but they know not everyone has that kind of family support. Consequently, Bowen decided to make a generous planned gift to UIC.

“Every little bit helps,” she affirms. “I love this department, and I believe in this department.”

Bowen hopes her gift will inspire others to make a gift to the college, so the overall impact is even larger. She hopes to alleviate the burden of debt and loans that so many students take on in order to pursue higher education.

“I would ask you to think about friends who struggled financially—I know we all had friends or colleagues like that,” she shares. “Think about the young adults who are struggling like that today.”

It’s not just about financial need, Bowen says. It’s also about preparing the next generation of leaders in these important fields.

“Students leave the Department of Kinesiology and Nutrition with a strong education, really prepared to go out and serve,” Bowen says. “We’ve been committed to that over the years, and we are still committed.”

Bowen’s gift will undoubtedly lengthen the already long list of students she has influenced during her career. This legacy is not one that can be measured in any simple way, but a hint of its lasting impact can be gleaned from Bowen’s gumption and generosity, from her meaningful contributions to research, from her dedication to the Department of Kinesiology and Nutrition, and from the many lives she touched along the way.